Paul Hammant's Blog:

Google's Scaled Trunk-Based Development

Update: See the new resource site for Trunk-Based Development called, err, TrunkBasedDevelopment.com and make sure to tell your colleagues about it and this high-throughput branching model.

Google’s Published talks/info

My knowledge about how Google developed software ended in 2009. They have talked publicly a number of times on the topic though:

- Pat Copeland: Google’s Innovation Factory and how testing adapts (Apr 2010)

- Ashish Kumar: Development at Google (Dec 2010)

- Nathan York: Tools for Continuous Integration at Google Scale (Jan 2011)

- Michael Barnathan, Greg Estren & Pepper Lebeck-Jobe Building Software at Google Scale Tech Talk (Mar 2012). These guys go deeply into the directed graph nature of builds

- John Micco: Tools for Continuous Integration at Google Scale (Aug 2012)

- Ari Shamash at GTAC 2013: Evolution from Quality Assurance to Test Engineering. Ari goes further than Ashish and the others into the “Test Engineering” excellence his team does and why that’s a formal group beyond DevOps.

All these videos are great. There’s so much to see in them, particularly the slides with charts in them and the chatting about them. Watch the videos!!

There’s also a blog dedicated to their DevOps:

Welcome to the Google Engineering Tools blog!

Trunk based development

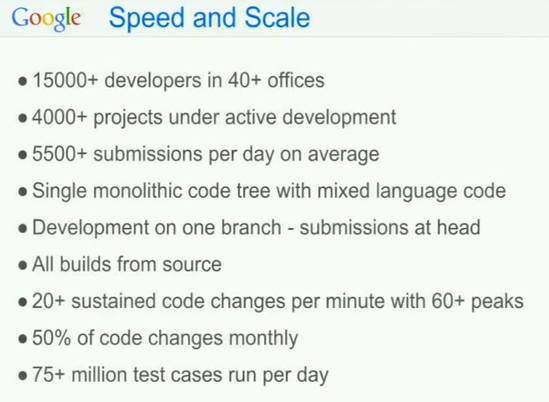

In the materials above, these Googlers talked about working on HEAD, and that checkins happen to HEAD at all times. Ashish says trunk a few times towards the end in a Q&A section, and he does mention an avoidance of branching for ongoing development (nothing to do with releases per se). So it’s official, Trunk-Based Development (TBD) is what Google do, and boy do they scale it!

Things specific to Google

(from John Micco’s 2012 talk)

A shared supercomputer for compilation

Note: Effectively a shared supercomputer!

Google have a lot of tooling for individual developers at the workstations, validations that somethings ready to commit (integrate into shared trunk), and the formal integration/merge/commit itself (because some time may have elapsed since that prior validation).

They have a “Distributed Builds” capability that’s shared by all of those. In layman’s terms it is effectively a supercomputer for the compilation (and unit-test execution) phases. It features and “Object Cache” and an “Action Cache” that can leverage someone else previously doing the same thing(s) so that results of the build are pulled in quicker. Time is saved for the developer in question, but they are also able to calculate a saving in terms of execution cost (CPU seconds for one).

Ashish talks of teams needing to depend on a common thing - Socket. Let’s call it s0ck3t so we think of it as a module rather than a concept. Two different developers in two different teams (say Gmail, and GoogleCheckout) have dissimilar technologies, but at the lower level have shared services. In our hypothetical example they both depend on s0ck3t. For their work in progress, neither developer has actually made modifications to s0ck3t. It is just in their directed graph of things they need to build and test before they can run the app (or commit the change). If one developer has build s0ck3t for the trunk at revision #12345 and the other developer minutes or hours later needs to do the same, then the supercomputer can do an optimization and give him/her build results (including object code) from the earlier build.

Avoidance of ‘clean’

Ari mentions in his talk that the whole system is designed to build incrementally, and not require ‘clean’ at any stage. Provable directed graphs of things that should consequentially be rebuilt, are needed for that. Their source setup makes that doable. For the rest of us in Maven land (or equivalent), there are moments when you’re driven to do ‘mvn clean install’ by superstition more than necessity. In many of the talks above, the avoidance of ‘clean’ is cited as a guiding rationale for the custom tooling Google have done.

Huge tooling around pre-commit goodness

Mondrian is what Google use for code reviews internally. Here is a 2006 article on that. At least it was in use at the start of 2009. Many other aspects of their pre-commit tooling have been discussed, but this is the key piece. As you ‘pre-submit’ a Perforce change list for review, a daemon side of Mondrian kicks in and takes your pending change list and runs it through multiple tests, adding more data to the Mondrian code review for that change. This is all available to the developer before they go as far to submit something for review, which is good as most people like to fail in private.

If someone were to change s0ck3t on its own in a change-list and push that into Mondrian for review, the consequential build would pull in all that could be impacted from the entire trunk. That could be many hundred of other modules for a huge range of site/apps that could have different release schedules. It does not matter when the release would go out for those individual pieces. We want to know about the potential breakage right now. Jez Humble reminds me that CI is about earliest possible integration news, and that Trunk is the best foundation to deliver that. I can’t remember how enthusiastic notifications of breakages were, for impacted downstream modules broken in a single commit - imagine emails being sent 300 other teams: “footle tried to break Adsense with commit #13456”. Without one trunk for each module (or worse), you’d need to depend on recently binary artifacts for the same directed graph traversal, and it would be infinitely harder to guard against false-negative and false-positives. Google know exactly what they are doing with “all build from source every time, in one trunk”.

Humans in the workflow at the pre-commit stage

There are armies of people willing to do code reviews. These developers, however, have regular teamwork to get on with, and reviewing code could be seen to detract from that. It is in their culture to code review though. Not just things that are happening to the code you’re assigned to nurture, but to arbitrary bits of the system. Again, Mondrian is the starting and ending point for this.

Incidentally, Google released Rietveld, and Gerrit was an independent attempt to recreate Mondrian before that. There are others in the commercial space of course.

DevOps Analytics

Both the videos about show much data analysis of commits, attempt to commit, builds, breakages, remediation (etc). Google knows how much it can save for identified problems, and can work out if it is cost-justifiable to develop something for that.

In many companies, good ideas might not get past managers, even with accompanying cost-justification. That’s not a problem in Google as developers have 20% time, meaning they can try something for the benefit of the company without the formal approval gates needed for a funded effort. There are well known apps like GMail, GTalk, Google News and AdSense coming out of 20% time, but there’s as much if not more coming that are not products/apps/services as such, but do improve developer throughput in tangible ways. In that way, an improvement to tooling could go on to get formal budget after it has become successful.

“Owners files”

Let’s talk about s0ck3t again. There’s a directory in the trunk for it’s code and tests. It has an small team that looks after it, and are the notional owners of it. One would hope it is stable, and that the team in question looks after many similar pieces. Either way, developers can make a change to any of the source files in s0ck3t, while doing work that has business value. They need the explicit authorization of the one of the owners of the module to get that commit in. Mondrian serves as the place that happens. While it is working out if there is sufficient karma for the commit proceed, it takes into account the contents of the owners file. Owners files are in the module’s directory and under source-control of course. Though the owners file is visible to all, only their owners can change them (or the perforce administrators).

In common with other TBD companies

There are more than these two aspects that they have in commit with other trunk based development teams, but these were the two mentioned in the talk:

Committing to anything

They have pulled back from “Common Code Ownership” an use the owners files mentioned above. Mondrian and tooling are an effective guard against commits that are not right. There is the potential for anyone to commit to anything though. There’s no officiousness around processing the submissions: “YOU should not commit to this at all” is not the attitude the reviewers, while there may be criticism of the actual content of the change list.

Diamond Dependency Worries

Ashish mentions Guice at the end of his talk (54.5 mins). The jar is centrally available (not disclosed how) to all things in the trunk that depended on it. They can only have one version of Guice for everything in the entire trunk. For example Gmail and GoogleCheckout are not allowed to depend on different versions in trunk (don’t know if they do or don’t). The reality of different release schedules are that different versions of Guice could concurrently be in production, but that’s different. Thus, a single change-list would upgrade guice for everyone, and there would be no broken build in any way afterwards. Interestingly Guice was made by Googlers, but is open source so is treated as “third party”, unlike the s0ck3t we talk of that could be open source (I guess), but is not, and is therefore in the trunk as source.

Merge conflicts

Merge conflicts rare (Q&A at the end of Ashish’s presentation). Merging to working copy is, of course, the merge individual developers typically encounter for TBD. If you have kept abreast, it is typically painless as Ashish mentions. If someone were to rename a whole directory (an example of one type of refactoring), then “merge-through-rename” is the feature of the source control package you really want.

Release Branches

Ashish mentions in his talk (52 mins in) that releases are made from branches cut from the trunk, and that cherry picks may happen after that (to production harden the release). Obviously each product team maintains it’s own release schedule.

Other Tidbits

Biggest Perforce repo

Google’s Perforce usage is apparently the largest single repository worldwide. In other words, the worlds biggest trunk. I’d like to know how many gigabytes that is for HEAD of everything.

Build language

Ashish talks of an intention to open-source their build language. I’ve not seen it yet, and GoogleSearch isn’t finding it for me. Here was a quote from Ashish on open sourcing the build language:

“Make and others are extremely restrictive/problematic as the dependency information is not exact in those … The more exact you can get, the more hermetic your build therefore you can paralelnize and distribute; So we would like to contribute that back”.

Twenty one minutes in to the excellent Barnathan/Estren/Lebeck-Jobe tech talk there’s a glimpse of the build language.

Some years ago, the Selenium2 team gravitated around CrazyFun which is highly reminiscent of the build language Google used internally (more later).

A few more words on Facebook

I’ve blogged twice on TBD at Facebook this year. Simon Stewart (ex ThoughtWorks, ex Google) talks some more about Facebook in his presentation some hours after Ari’s one on Test Engineering at GTAC. To see his section of the first video: fast forward the slider to 7 hours, 17 minutes. Facebook have one trunk for ‘www’, one for Android and one for iOS apps (video: 8h:01m). Whereas the www trunk was Subversion (last I heard), the Android one is in Git and has a workflow that includes a ‘master’ and ‘stable’ branch. If they are sharing code between iOS, Android, and www they are implicitly doing so in a way other that a relative source directory.

Directly after that Simon is asked a closing question by Noah Sussman “… so why no pre-commit hook?”, and Simon answered “because we have not had the need for it”. There’s an implicit ‘yet’ in that language, that he goes on to elaborate before closing. Smaller Agile teams too, will try TBD without too much pre-commit tooling, and use Continuous Integration & speedy rollback as the safety net, as well developer promise to do the right thing before committing.

Buck

Buck was mentioned too in Simon’s GTAC presentation (at the 7h 33m mark). It is a build technology they’ve launched that also works well for TBD teams: http://facebook.github.io/buck and like Google’s unreleased one was felt to be advantageous over existing open-source technologies. It is similar in design to CrazyFun as mentioned above.

Comments formerly in Disqus, but exported and mounted statically ...

| Thu, 09 May 2013 | Samuel Falvo II |

When I worked at Google back in 2007, trunk was close to 2.5GB in size, as I recall. My memory may be fuzzy though. | |

| Fri, 10 May 2013 | gongzhi |

Based on my understanding, there MUST be lots of tools/rules to support trunk based development. | |