Paul Hammant's Blog:

Scoring Continuous Integration

So we’ve know for a more than a few years that software development teams will claim they are doing “Continuous Integration”, but are not really. ThoughtWorks confirmed this in a SnapCI related survey last year. That survey highlighted that 60% of teams are doing multi-branch development, and a greater percentage don’t truly understand Continuous Integration. In short teams were doing something continuously, but it might have been closer to isolation than integration.

Context

For Continuous Integration (CI) to be an honest claim, for a team, there needs to be a cadence around developing stories, and a bunch of prescribed activities for developers between starting work on a story and checking it in. In the early days, CI was only practices as there wasn’t a CI daemon double-checking developer commits back then. Trying to apply INVEST to the story was a good start. frequently keeping up with HEAD of the trunk/master was another. Doing a series of baby commits towards of completion of the story was yet another (as long as each one was eminently go-livable). but at the moment of checkin (commit/push these days), developers had to be 100% sure that the very latest development version of everything would work with their pending commit. That’s the integration bit. Before Extreme Programming (XP), that’d be a nightly activity (even if automated or at least single-click). With XP it became an “all day” activity too - a pre-commit ceremony that ensured the team could sustain highest throughput.

With source control systems (regardless of branching model) the best practice pre-commit activities are (in Git terms):

git commit -m "story 123: blah blah blah"

git pull

# resolve merge conflicts

# run the fullest build you can, and if that passes ...

git push

^ There are alternates with git stash and git rebase, but it is all the same in the end.

It is possible to do CI for an application that pulls components/services from multiple builds for multiple source-control repos. The integration aspect of CI remains the same though - what you do pre-commit, and what Jenkins does in its daemon is to pull together the latest development versions of all of those components and services and an integration test for them. ‘Latest’ means to HEAD revision, in source-control terms.

For CI to be done correctly, regardless of the numbers of source-control repos that have buildable things, you’ll only want to track one branch (‘master’ for Git) for each. Teams doing development on multiple active branches (ignoring short lived feature branches) are not continuously integrating (as mentioned before). If that is true, it would be cool to be able to score a distance from true CI, or have a grade somehow.

Scoring your team’s branching skills

Here is a formula: for each branch that:

- is not trunk or master (the single branch that grows in value year after year)

- has commits that are not yet on trunk or master

- is going to be merged back to trunk or master at some point in the future (cherry-pick or sweeping merge)

For each of those:

- calculate the number of hours between the earliest divergent moment and the current HEAD revision of trunk/master. For the elapsed time, add 8 for each full working day (no score for weekends or bank holidays).

- then divide that by 16 (two days for an ‘optimal’ average story size). Don’t argue with that - the famous C3 project (1996/7/8 using Smalltalk) had an average story size of 1 day (8 working hours).

- then multiply that by the number of committers on the branch in question. A pair of committers doing pair-programming still counts as 1, by the way.

Finally:

- average those numbers for the qualifying branches (the trunk/master itself scores at 0).

- divide that number into 100 and lose the decimal positions.

That is the ultimate score and ideally it should be less 90 or more. Much less 80 and you’re not doing the trunk-based development effectively. Much less that 30 and you’re not doing the source-control aspect of Continuous Integration at all, or your stories are too big which is different cause for concern.

In reality, there are more factors for a score. You could be doing trunk based development the old fashioned way - just a trunk or a master branch and everyone taking their turn to commit/push to that. With no concurrently active branches, you could argue that the score for the team/repo is 100, which sounds good. The reality though is that each developer’s working copy or local workstation clone is still an effective branch. If so, the allegation that it is more isolation than integration could still be true in some cases, but harder to determine. Maybe scoring has to extend to developer’s workstations. Specifically: branches and uncommitted working copy on the workstation.

Worked examples

Branch for release

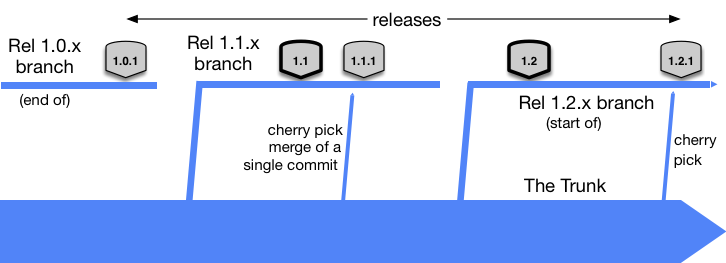

One variant of Trunk-Based Development is “branch for release”.

The score appears to be 100 (special handling) as none of the 2.5 release branches depicted above will be merged back to the trunk. Thus they are disqualified for scoring based on rule #3 (above). We’re remembering that we only fix bugs on the trunk and cherry-pick to the release branch.

In reality, though, the team either has short-lived feature branches, or working copy on developer workstations. And those should affect the score somehow (as mentioned).

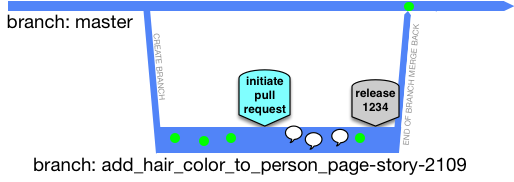

Short-lived feature branches

Made possible by GitHub, it is important to know that not all “Pull Request” branches/forks are short-lived. Let us assume that the dev team in question can truly deliver the “short-lived” aspect of this though:

The score could be anywhere from 90 to 200 for such branches, if things are zipping along.

Unsolicited Pull Requests in Opensourceland

We should not score these. They are a completely different CI “contract”.

This is part of the power of open source development in the GitHub era. People making contributions don’t send patches any more. They fork your repo without permission make their changes then donate them back again to you in a “pull request”. That is not on a real branch of your repo, it is on an effective branch (really a different repo). GitHub keep track of that in their MySql/Postgres database and it is up to you acknowledge and process the PR in some way. Or ignore it if you want. Most likely they cannot and should not count towards you branching score. At least not in the previously described way. Even when they come back into master (if), then that could be after a delay that’s perfectly reasonable. It seems that these developers are “surprise team mates”, rather than regular ones. More thinking needed perhaps [a May 3rd ‘17 addition].

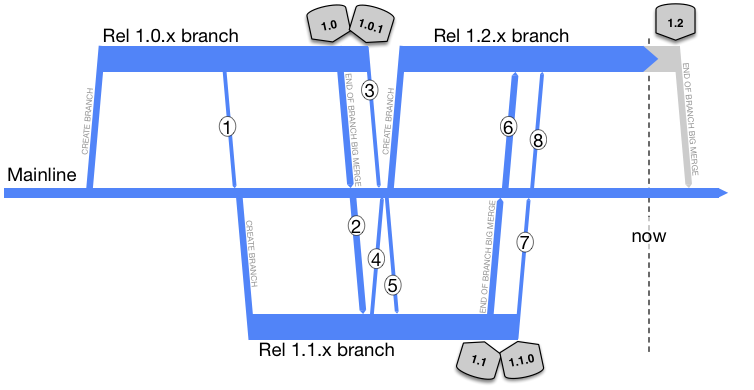

Mainline

The old branching model popularized by ClearCase over fifteen years ago:

Say there’s four (planned) releases a year, and 20 developers in the dev team.

1st Jan 2017 to 1st April 2017 (three months) is 62 business days. Times 8 (eight hour days) is 496. Divide that by 16 is 31. Times that by 20 (the number of devs) to get a number of 620. That’s just for one of the branches. If there are two of those long running branches in flight at the same moment in time, the 20 devs could be split between them 50:50 or 70:30 so the 620 number would be about the same. Divide that into 100, and you’ll get 0.16 score (0 if rounded). As bad as it gets.

A more comprehensive CI score.

Additional factors are needed I think.

There is one that is something to do with how long it would take a team to release HEAD without gambling on the number of defects. Integration defects specifically, but any defect not in the last release too. You see, those Mainline teams have weeks where the build doesn’t work at all. If the CIO came in and said “we’re going live in four hours” those teams would have to hack dozens of things to redefine “green” for the build and even then they would have to preemptively look for new jobs.

One factor should be based on the straight interval between commits to trunk/master for a developers. Shorter is better. Related could be the size of the commit (bigger = worse), but you’d want to give a get out jail card for pure refactorings, of course.

Another is around rating the multiple couplings of components being integration tested. I myself like service virtualization (with safety checks) for the earlier stages of a build, but most materials around DevOps these days suggest “production like” as the rule for test automation. I love the speed and “shift left” nature of such wire-mocking, but if you’re counterbalancing that with an additional “shift right” automated test build step that is full-stack (end to end) and relegating that daily build only, that would surely lower your CI score.

I mentioned story size earlier. The highest throughput team living the CI dream, coincidentally have small stories to work on. Sure there are outliers, but if you discard the expended effort spent on those, you can arrive at figure that for the team describes the average amount of time spent on a story. Smaller is better, and we should lament that it is harder to hit the one-day average of the early Extreme Programing teams.

Lastly, two subtle “after the event” factors: for a pull-request that would land on the trunk or master, how long before the a) the first round of code reviews are done, and b) the CI daemon has weighed in with its opinion. The former is “continuous (code) review”, the latter is still useful even if the community thinks CI is the daemon. Read Martin Fowler’s ContinuousIntegrationCertification on that.

Talking of CI daemons - teams doing per-commit CI verifications should score better than teams batching commits. Maybe that should simply be an “average number of commits per build” thing, where 1 is the right answer. Teams that fix build breakages quickly should also score better than ones that don’t. Having an auto-rollback is the simplest thing to do there and score well. From Martin’s article (citing Jez Humble) an average number of minutes from breakage to fix (as adjudicated by the CI daemon). I’m not sure how to make that a 1 to 100 range though.

Score or grade?

A score is a number up or down a fixed range. Classically that would be 0 to 100. A Grade would (most often) be ranges within that. Say ‘A’ for 86 to 100, and ‘B’ for 68 to 85 and so on. Our CI score has a semblance of a 0-100 range but very successful teams could go way above 100. Maybe that is just what we have to accept. And we also have to accept special handling for the divide by zero possibility of a ‘no branches other than trunk’ situation - with a designation of 100 for the score.

Comments formerly in Disqus, but exported and mounted statically ...

| Wed, 10 May 2017 | Roy Inganta Ginting |

Thanks for the blog post Paul. I am trying to understand how to calculate short-lived feature branches. The hypothetical case above score badly even though all of the branches are short-lived (2 - 3 days per branch). Thank you. | |

| Wed, 10 May 2017 | paul_hammant |

The two developers were pair-programming, at the same workstation committing together, or two people concurrently push/pulling to the same short-lived feature branch from their own dev workstations? If it is the former you get to score that as "1 developer", not 2. But I'll trust that you spotted that already in the notes and that you have 2.33 as you say. The next calc is 100/2.33 not the inverse of that (as you did it). 42.91 or just 42 without the decimal positions is the score. Seems to me that you're only one tweak away from a better branching place - **get the devs to pair program on their short-lived feature branches**, and move that score up much closer to 100. The stats have been done a few times - pair-programming cheapens mistake/defect remediation and results in better code generally, will a long term debt-reducing effect. | |